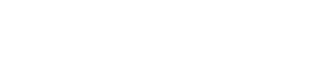

Industry observers, investment bankers and consultants agree: The auto industry is caught up in a shift away from the traditional business of selling vehicles & parts to providing mobility centric services to improve how people and goods can move from point A to point B (see Figure 1, Schlueter Langdon 2018). The shift is epic, because firstly, services are a very different type of business – with subscriptions and incremental annuity cash flows, new operations and software automation (Rayport & Jaworski 2004, Chase & Dasu 2001, Chase & Garvin 1989). Secondly, the shift appears to be rapid – in less than two vehicle generations – and enormous in size. For incumbents – original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), suppliers, and channel partners alike – continued success requires building up a different business system while “keeping the wheels on the bus.”

The auto-less auto company: Powershift to data

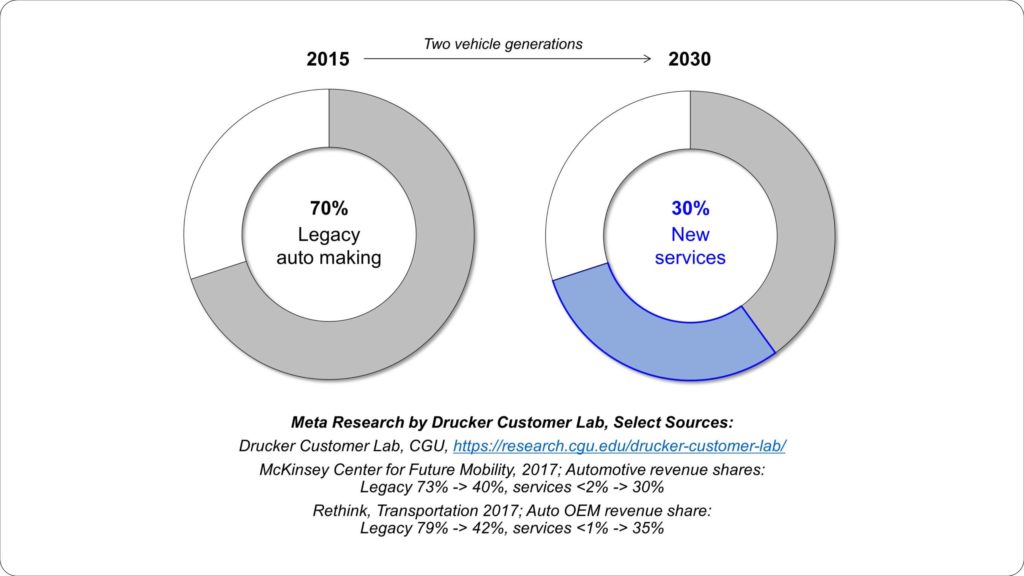

Investors agree: Data-driven services beat making things big time. Power – and profit – seem to be shifting from the vehicle to data (see Figure 2, Schlueter Langdon 2019). It sounds provocative – particularly to auto people – but it’s neither magic nor a surprise. We have seen it before in content businesses ranging from newspapers to music (Meeker 2018). Newspapers felt well protected behind printing presses and last mile delivery only to be outflanked by digital and data ([digital entrants] “exploit individual consumer profiles and behavior data to increase customer satisfaction, loyalty, repeat purchases, and cross-selling opportunities,” Schlueter Langdon 2002, p. 52). While paper-based publishers went from top to bottom, data hogs like Google and Facebook arose to usurp marketing budgets with next generation data-driven services. The switch did not happen overnight, and there are always exceptions but even storied brands like Time Magazine, Newsweek and The Washington Post had to be rescued by philanthropists (by Salesforce’s Marc Benioff, Harman’s Sid Harman, and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, respectively).

Data: A big misunderstanding … puzzle headedness … neglect

In 2006 Clive Humby, a mathematician and architect of UK retailer Tesco’s club and loyalty card (and co-founder of consumer data science pioneer Dunnhumby, spoke of “data as the new oil” at the Association of National Advertisers’ marketer’s summit at Chicago’s Kellogg School of Management (Arthur 2013). The one part of his oil analogy, that data may be as valuable as oil has caught on – although data is not even used up in consumption like oil. The other part about the refining effort … well, no so much. Humby’s analogy suggests that in order to prepare raw data into a refined data product for analytics or ready for artificial intelligence, so called AI-ready data, it may take (a) extensive refining (for example, “filling in” or imputing missing data) and (b) at an industrial scale with large platforms comparable to massive refineries for oil. For plain data storage and processing this refinery analogy appears to correspond very well with observations in the field, specifically the explosive growth of the cloud business. Launched with Amazon’s Elastic Compute Cloud in 2006 the business is already highly concentrated at an early age with only three hyperscalers dominating most of the business: Amazon’s Web Services (AWS), Microsoft’s Azure, and Google’s Cloud Platform (GCP). As of end of 2018 these top three vendors accounted for 60% of the business, the top 10 for nearly 75% (Miller 2019).

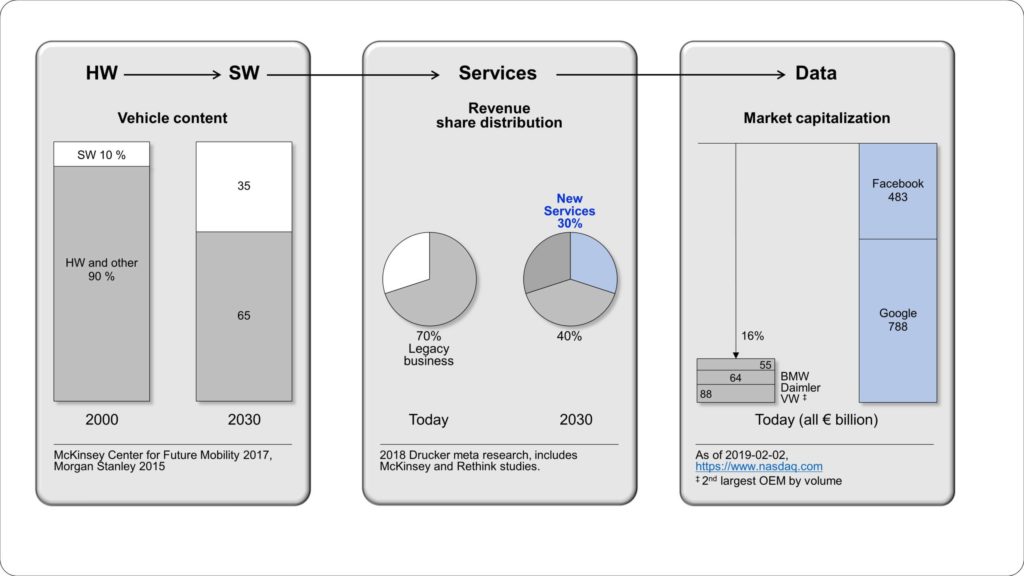

If you can’t measure, you cannot manage

The 2020 Coronavirus tragedy unexpectedly put data in the spotlight and turned it into front-page news. All of us were suddenly debating new variables, such as infection rates. And suddenly key concepts to evaluate the quality of data science, namely reliability (consistency of measures), and validity (accuracy of measures) made sense to everyone. The crisis pulled data and its complexity out of the shadow and into the limelight. In the past, if I asked an audience who had taken a statistics class, all hands would go up. But no one would volunteer to quickly explain a t‑test. If I asked about data, nobody had taken a class, but everybody would be eager to explain it. So, it was easy to peddle stereotypes, omitting deeper issues, such as data harmonization (e.g., Schlueter Langdon & Sikora 2019), sharing and pooling architectures, and data rights management and governance (e.g., Otto 2011). Even a supposedly straightforward task, such as sizing data, how to measure the quantity of data, has remained surprisingly tricky to this day. We know to buy eggs by the dozen, a pound of butter, and a liter of milk. But how do we buy data? Figure 3 illustrates the dilemma. And how to monetize data, or use it as “fuel” to “power” new “smart” services, such as seamless mobility, if we can’t even quantify data properly?

Data issues: Science, productization, business strategy and regulation

Data is widely seen as a key enabler of new, future, next mobility: “Open flow of data across infrastructure and user domains is an important enabler for smart mobility services and systems innovation” (European Commission 2017, p. 15). However, the challenges are formidable. They include:

- Data science issues, such as the aforementioned “metrics gap” with regard to data quantity, quality and information content.

- Data industrialization (Walter et al. 2007) or productization to make data affordable and data analytics scalable (“data as a product,” Crosby & Schlueter Langdon 2019; “data factory for data products,” Schlueter Langdon & Sikora 2019).

- Business strategy considerations: “The smart integration of tariff structures, data and user interfaces as well as the disposition of rolling stock […] requires new business models and scheduling, booking, navigating, ticketing and charging solutions” (European Commission 2017, p. 11).

- Regulatory updates: “Individual data privacy rights and the ownership of mobility and city data will need to be addressed and regulated to ensure both competition and freedom from illegal governmental or commercial surveillance” (European Commission 2017, p. 13–14).

Connecting the dots: IDSA for data, NPM for mobility, GAIA‑X for both?

Luckily, there are several initiatives that address various aspect of the many data issues, such as NPM for mobility in Germany, IDSA for data sovereignty in Europe and GAIA‑X for both.

- NPM, the National Platform Future of Mobility, was convened by the German government in 2018 in order to find a way forward for the auto business, the most important industry in Germany. It was launched by the Federal Minister of Transport, Andreas Scheuer, and is headed by the former CEO of SAP, Prof. Dr. Kagermann, “to develop multi-modal and intermodal paths for [… an] environmentally friendly transport system” (NPM 2020).

- The International Data Spaces Association (IDSA) counts 110+ member organizations and has defined an IDS reference architecture and a formal standard to be used for creating secure and trusted data spaces (Otto et al. 2019), in which companies of any size and from any industry can manage their data assets in a sovereign fashion. In order to cater to the specific requirements of a mobility data space a dedicated IDSA community is being created.

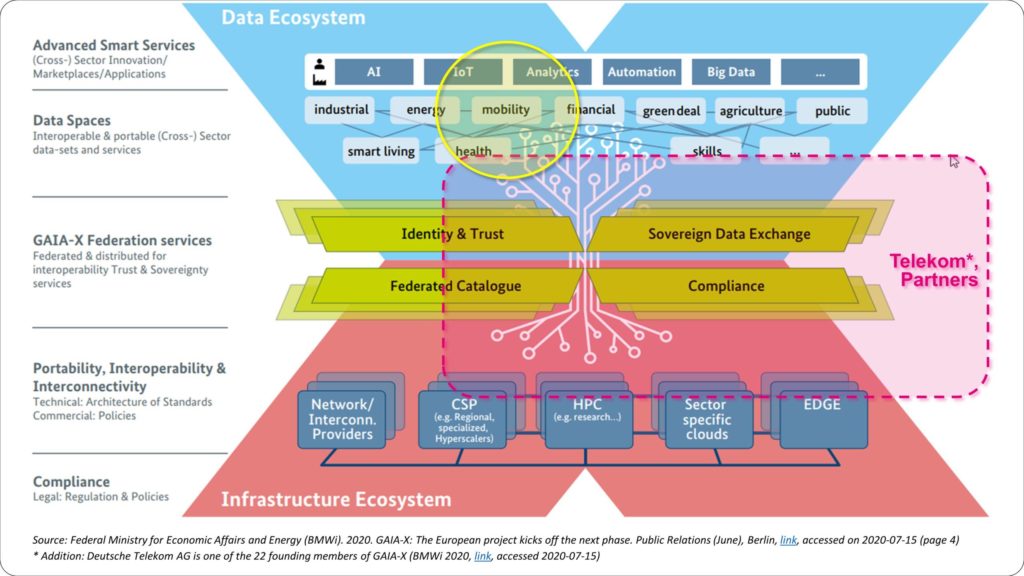

- GAIA‑X was unveiled in June 2020 by German Federal Minister of Economic Affairs and Energy Peter Altmaier and the French Minister of the Economy and Finance Bruno Le Maire to kick off the creation of a next generation, secure infrastructure for shared data or data pools or “spaces” in Europe. Why bother? Well, if AI is the future and some of the most successful AI needs lots of data – Big Data – then only big companies with big data will have a future. And small companies won’t. This is where GAIA‑X comes in, enabling data sharing with sovereignty using IDS among other techniques (BMBF 2019).

How to connect the dots? Well, stay tuned. NPM is said to be working on a real life laboratory to present results on new, future, next mobility for the ITS World Congress in 2021 in Hamburg (NPM 2020). Watch for announcements soon.

References

Arthur, C. 2013. Tech giants may be huge, but nothing matches big data. The Guardian (August 23) (link)

BMWI, Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. 2020. GAIA‑X: The European project kicks off the next phase. Public Relations (June), Berlin (link)

Chase, D., and S. Dasu. 2001. Want to Perfect Your Company’s Service? Use Behavioral Science. Harvard Business Review (June): https://hbr.org/2001/06/want-to-perfect-your-companys-service-use-behavioral-science

Chase, D., and A. Garvin. 1989. The Service Factory. Harvard Business Review (July-August): https://hbr.org/1989/07/the-service-factory

Crosby, L., and C. Schlueter Langdon. 2019. Data is a Product – Managers who conceptualize data as a product can maximize its multi-functional potential. Marketing News, American Marketing Association (April 24) (link)

European Commission. 2017. Smart mobility and services – Expert group report. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Directorate H Transport, Unit H.1 Transport strategy (EUR KI-01–17-928-EN‑N): Brussels

Meeker, M. 2018. Internet Trends 2018. Code Conference. Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (May 30): https://www.kleinerperkins.com/perspectives/internet-trends-report-2018/

Miller, R. 2019. AWS and Microsoft reap most of the benefits of expanding cloud market. Techcrunch (February 1st) (link)

Otto, B. 2011. Organizing data governance: Findings from the telecommunications industry and consequences for large service providers. Communications of the AIS 29(1): 45–66

Otto, B., S. Steinbuß, A. Teuscher, and S. Lohmann. 2019. Reference Architecture Model Version 3.0. International Data Spaces Association (April), Dortmund (link)

Rayport, J, and B. Jaworski. 2004. Best Face Forward. Harvard Business Review (December): https://hbr.org/2004/12/best-face-forward

Schlueter Langdon, C. 2019. The Auto Power Shift to Data – From Asteroid to Data Sandwiches and Exchanges (Auto 2). Working Paper (WP_DCL-Drucker-CGU_2019-01), Drucker Customer Lab, Drucker School of Management, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA (link)

Schlueter Langdon, C. 2018. The Auto Service Shift and 7 Gaps (Auto 1). Working Paper (WP_DCL-Drucker-CGU_2018-05), Drucker Customer Lab, Drucker School of Management, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA (link)

Schlueter Langdon, C., and R. Sikora. 2019. Creating a Data Factory for Data Products. Proceedings of the 18th Workshop of E‑Business at ICIS Munich (December)

Schlueter Langdon, C., and M. J. Shaw. 2002. Emergent Patterns of Integration in Electronic Channel Systems. Communications of the ACM 45(12): 50–55

Walter, S.M., T. Böhmann, and H. Krcmar. 2007. Industrialisierung der IT — Grundlagen, Merkmale und Ausprägungen eines Trends. HMD Praxis der Wirtschaftsinformatik 44(4) (August): 6–16